by MICHAEL LYONS

Creighton Digital Storytellers

As mental health continues to be a growing concern in the United States, attention continues to shift toward children and adolescents, as the National Mental Health Institute reports that 50 percent of all lifetime cases of mental illness begin before age 14, making parents increasingly more skeptical of asking “Is this just a stage?”

This line of questioning typically persists for too long. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the average delay between onset of symptoms and intervention in mental illness is 8-10 years, allowing time for conditions to potentially worsen. Numerous studies have been completed, giving researchers and care providers a wealth of information on the subject, the question now is, “what don’t we know?”

Embed from Getty Images“We know quite a lot about the risk factors associated with poor mental health,” said Creighton University Psychology professor Amy Badura Brack. “I would like to see more attention devoted to how we can help youth develop resilience to protect them in the face of stressors.”

The Hastings Center Bioethics Research Institute explains that both biological factors, like genetics and brain chemistry, as well as environmental factors, such as stress and home life, play a role in mood and behavior — the most definitive symptoms of determining mental illness.

The challenge now is knowing whether these symptoms are normal child behavior or mental illness, and further determining which particular illness it is. Given how broad of a spectrum mental health is, it’s difficult to pinpoint one particular illness amongst the many, with overlapping symptoms and lack of objective evidence.

“Complex issues are multi-determined, so isolating the most important active ingredients in a large-scale problem or potential solution is challenging,” Badura Brack said.

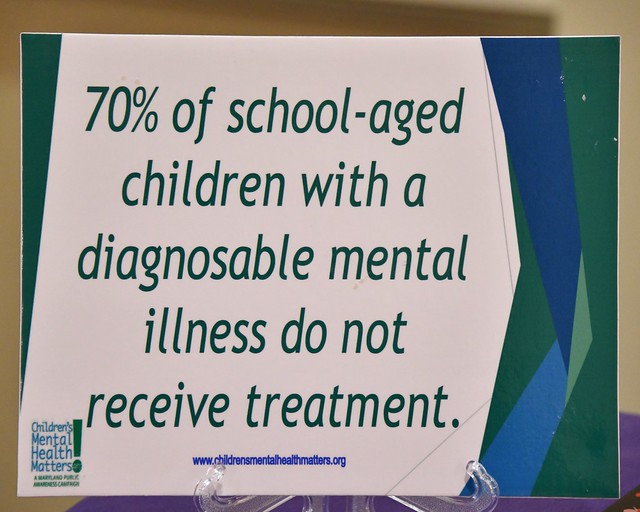

This broad spectrum has made treatment a difficulty for care providers as well. Research from the Great Rocky Mountains Study found that stimulant medications were being prescribed to more children without ADHD than to children with ADHD, and that 28 percent of children with ADHD were not receiving medication. In fact, later studies show that many children without ADHD are not receiving a diagnosis. In order to narrow this gap, school systems are taking additional measures to identify symptoms.

“We’re finding that if services are not provided, kids often go without it,” said Dr. Nancy Bond, Omaha Public Schools Direct Supervisor for School Counseling. “The role of educators is expanding as the needs of our students increase.”

OPS has increased the presence of social workers in its schools, with more than 40 on staff in the district today. Additional training has been provided to teachers in schools in order to better help identify symptoms of mental illness and limit the onset of diagnosis.

State legislation was passed in Nebraska for mental health in schools in 2014, with Nebraska LB 923 requiring training on suicide awareness and prevention.

Recent attempts for national legislation for mental health programs in schools have failed, but the current prevalence of the issue suggests that discussions are not going away.